Thrombophlebitis

| Thrombophlebitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Phlebitis[1] |

| |

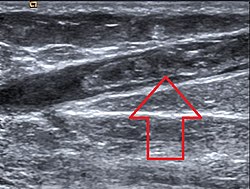

| Ultrasonographic image showing thrombosis of the great saphenous vein. | |

| Specialty | Cardiology, emergency medicine, interventional radiology, infectious disease, oncology |

| Symptoms | Skin redness[1] |

| Risk factors | Smoking, Lupus[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Doppler ultrasound, Venography[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | cellulitis, deep vein thrombosis, erythema nodosum, lymphangitis, lymphedema, tendonitis, septic thrombophlebitis |

| Treatment | Blood thinners, Pain medication[1] |

Thrombophlebitis is a phlebitis (inflammation of a vein) related to a thrombus (blood clot).[2] When it occurs repeatedly in different locations, it is known as thrombophlebitis migrans (migratory thrombophlebitis).[3]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]The following symptoms or signs are often associated with thrombophlebitis, although thrombophlebitis is not restricted to the veins of the legs.[1][4]

- Pain (area affected)

- Skin redness/inflammation

- Edema

- Veins (hard and cord-like)

- Tenderness

Complications

[edit]Complications of thrombophlebitis include infection of the vein, concurrent thromboembolism, or recurrent thrombophlebitis.[5]

Infection of the vein can include symptoms such as high fever, redness of the site that can spread, and purulent drainage, making it septic or suppurative thrombophlebitis.[6][7] Septic thrombophlebitis is not common if there has not been a history of recent disruption of the vein such as catheterization or venipuncture. If left untreated, it can cause septic shock and death.[citation needed]

A deep vein thrombosis can accompany thrombophlebitis by extension of the original thrombosis. Factors that can also predict DVT with concurrent SVT include age >60 years, male sex, bilateral SVTs, presence of systemic infection, and absence of varicose veins.[8][9]

Causes

[edit]

Thrombophlebitis causes include disorders related to increased tendency for blood clotting and reduced speed of blood in the veins such as prolonged immobility; prolonged traveling (sitting) may promote a blood clot leading to thrombophlebitis but this occurs relatively less.[1][4]

Long term use of intravenous catheters, intravenous antibiotics, and infusion of vein-irritating substances (such as potassium chloride or sclerotherapy agents) can contribute to development of thrombophlebitis. Larger size, longer duration, and some sites of insertion of catheters are risk factors for developing thrombophlebitis.[10][11]

Patients with varicose veins, current or immediately post-pregnancy, advanced age, malignancy, recent trauma or surgery, autoimmune or infectious diseases including lupus and antiphospholipid syndrome, obesity, history of venous thrombosis (DVT), respiratory or cardiac failure, and history of or current exogenous estrogen use can increase risk of developing thrombophlebitis.Those with familial clotting disorders such as protein S deficiency, protein C deficiency, or factor V Leiden are also at increased risk of thrombophlebitis.[12][13]

Specific disorders associated with thrombophlebitis include superficial thrombophlebitis which affects veins near the skin surface, deep vein thrombosis which affects deeper veins, and pulmonary embolism.[14]

Thrombophlebitis can be found in people with vasculitis including Behçet's disease.

Migratory thrombophlebitis, which is when there is repeated thrombophlebitis of multiple different sites that moves around the body, is strongly associated with pancreatic cancer or other malignancies. This is also known as Trousseau syndrome.[15]

Pathophysiology

[edit]Thrombophlebitis first develops as a thrombus, or blood clot. Virchow's triad helps describe how blood clots can begin to form in veins with increased turbulence, slowing of blood flow, or injury to the venous wall. From there, a microscopic thrombus becomes larger because it triggers inflammatory responses in the body that causes platelets to adhere. A large thrombus in a superficial vein is what we call thrombophlebitis.[12]

Diagnosis

[edit]The diagnosis for thrombophlebitis is primarily based on the appearance of the affected area. Frequent checks of the pulse, blood pressure, and temperature may be required. If the cause is not readily identifiable, tests may be performed to determine the cause, including the following:[1][12][4]

- Doppler ultrasound

- Extremity arteriography

- Blood coagulation studies

- Imaging for underlying malignancies (such as CT or MRI)

- Genetic testing for blood clotting disorders such as antiphospholipid syndrome, protein S deficiency, protein C deficiency, or factor V Leiden

Prevention

[edit]Prevention consists of walking, drinking fluids and if currently hospitalized, utilizing aseptic technique to place and change IV lines.[1] Walking is especially suggested after a long period of being seated, particularly when one travels.[16]

Treatment

[edit]

The main treatments for thrombophlebitis include utilizing pain control (such as NSAIDs), application of heat, and use of anticoagulants. Compression stockings may help prevent these for people with varicose veins. If the cause of the thrombophlebitis is due to something else, such as underlying infection or malignancy, addressing these causes can help treat and prevent future episodes.

In general, treatment may include the following:[1][4][17]

Anticoagulation is thought to help prevent future incidents of venous thromboembolic complications such as deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, but the treatment is often debated.[18] Fondaparinux is thought to be the most effective of the anticoagulants for this purpose. However, anticoagulation is not appropriate for those with underlying thrombocytopenia or risk of major bleeding.

For septic thrombophlebitis, treatment includes use of intravenous antibiotics, possible anticoagulation, and evaluation by a surgical team for possible intervention.[6] If there is an abscess present, it may need to be drained surgically.

Overall, prognosis is positive if patients are low-risk at baseline. A very low number (less than 1% in one study) of patients go on to develop other life-threatening blood clots such as deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism within 3 months.[19]

Epidemiology

[edit]Thrombophlebitis occurs almost equally between women and men, though males do have a slightly higher possibility. The average age of developing thrombophlebitis, based on analyzed incidents, is 54 for men and 58 for women.[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Thrombophlebitis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 8 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ Torpy JM, Burke AE, Glass RM (July 2006). "JAMA patient page. Thrombophlebitis". JAMA. 296 (4): 468. doi:10.1001/jama.296.4.468. PMID 16868304.

- ^ Jinna, Sruthi; Khoury, John (2020). "Migratory Thrombophlebitis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31613482. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2020-02-29.

- ^ a b c d "Thrombophlebitis Clinical Presentation: History, Physical Examination, Causes". emedicine.medscape.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ Décousus, H.; Bertoletti, L.; Frappé, P. (2015). "Spontaneous acute superficial vein thrombosis of the legs: do we really need to treat?". Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis: JTH. 13 Suppl 1: S230–237. doi:10.1111/jth.12925. ISSN 1538-7836. PMID 26149029.

- ^ a b Lipe, Demis N.; Afzal, Muriam; King, Kevin C. (2025), "Septic Thrombophlebitis", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28613482, retrieved 2025-05-04

- ^ Mermel, Leonard A.; Allon, Michael; Bouza, Emilio; Craven, Donald E.; Flynn, Patricia; O'Grady, Naomi P.; Raad, Issam I.; Rijnders, Bart J. A.; Sherertz, Robert J.; Warren, David K. (2009-07-01). "Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 49 (1): 1–45. doi:10.1086/599376. ISSN 1537-6591. PMC 4039170. PMID 19489710.

- ^ Bergqvist, D.; Jaroszewski, H. (1986-03-08). "Deep vein thrombosis in patients with superficial thrombophlebitis of the leg". British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.). 292 (6521): 658–659. doi:10.1136/bmj.292.6521.658-a. ISSN 0267-0623. PMC 1339644. PMID 3081214.

- ^ Gorty, Satya; Patton-Adkins, Jeanne; DaLanno, Michelle; Starr, Jean; Dean, Steven; Satiani, Bhagwan (2004). "Superficial venous thrombosis of the lower extremities: analysis of risk factors, and recurrence and role of anticoagulation". Vascular Medicine (London, England). 9 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1191/1358863x04vm516oa. ISSN 1358-863X. PMID 15230481.

- ^ Heng, Shu Yun; Yap, Robert Tze-Jin; Tie, Joyce; McGrouther, Duncan Angus (2020-04-01). "Peripheral Vein Thrombophlebitis in the Upper Extremity: A Systematic Review of a Frequent and Important Problem". The American Journal of Medicine. 133 (4): 473–484.e3. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.08.054. ISSN 0002-9343. PMID 31606488.

- ^ Kristo, Gentian (2025-02-09). "Management of superficial venous thrombophlebitis associated with peripheral venous catheters: A review". Global Journal of Surgery and Case Reports. doi:10.5281/zenodo.14838429. ISSN 2998-8055.

- ^ a b c Czysz, Augusta; Higbee, Sheetal L. (2025), "Superficial Thrombophlebitis", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32310477, retrieved 2025-05-04

- ^ Philbrick, John T.; Shumate, Rebecca; Siadaty, Mir S.; Becker, Daniel M. (23 October 2016). "Air Travel and Venous Thromboembolism: A Systematic Review". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 22 (1): 107–114. doi:10.1007/s11606-006-0016-0. ISSN 0884-8734. PMC 1824715. PMID 17351849.

- ^ "Superficial Thrombophlebitis: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology". eMedicine. Medscape. 12 July 2016. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ Varki, Ajit (15 September 2007). "Trousseau's syndrome: multiple definitions and multiple mechanisms". Blood. 110 (6): 1723–1729. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-10-053736. ISSN 0006-4971. PMC 1976377. PMID 17496204.

- ^ Tamparo, Carol D. (2016). Diseases of the Human Body. F.A. Davis. p. 292. ISBN 9780803657915. Archived from the original on 22 July 2024. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ a b Raval, P. (1 January 2014). "Thrombophlebitis☆". Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.05368-X. ISBN 9780128012383. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ Duffett, Lisa; Kearon, Clive; Rodger, Marc; Carrier, Marc (2019). "Treatment of Superficial Vein Thrombosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 119 (3): 479–489. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1677793. ISSN 2567-689X. PMID 30716777.

- ^ Patel, Payal; Patel, Parth; Bhatt, Meha; Braun, Cody; Begum, Housne; Nieuwlaat, Robby; Khatib, Rasha; Martins, Carolina C.; Zhang, Yuan; Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta, Itziar; Varghese, Jamie; Alturkmani, Hani; Bahaj, Waled; Baig, Mariam; Kehar, Rohan (2020-06-22). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes in patients with suspected deep vein thrombosis". Blood Advances. 4 (12): 2779–2788. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001558. ISSN 2473-9529.

Further reading

[edit]- Sadick, Neil S.; Khilnani, Neil; Morrison, Nick (2012). Practical Approach to the Management and Treatment of Venous Disorders. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781447128915. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- Mulholland, Michael W.; Lillemoe, Keith D.; Doherty, Gerard M.; Maier, Ronald V.; Simeone, Diane M.; Upchurch, Gilbert R. (2012). Greenfield's Surgery: Scientific Principles & Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9781451152920. Retrieved 23 October 2016.